`

David Mack - To Write Boldly...

David Mack - To Write Boldly...

by John A. Wilcox

David Mack cut his Trek teeth on Star Trek : Deep Space Nine back in the nineties before making a name for himself as an award winning novelist. Mack has written many notable Trek novels & when I tracked him down to discuss all things Trek, he agreed without hesitation!

PS: What about the Star Trek universe first captured your imagination?

DM: To quote the character Russell Hammond from Cameron Crowe’s film Almost Famous, “To begin with… everything.”

I grew up in the early 1970s immersed in the syndicated reruns of the original Star Trek. I was only dimly aware of the Cold War world in which I lived, but the future of Star Trek felt real to me. I knew it was just a story, but it was a powerful one: a vision of a future humanity could choose, if it has the courage and the humility to do so.

Star Trek’s ethos of teamwork and friendship, its philosophy that compromise and diplomacy are better than violence, and its depiction of a galaxy filled with wonders awaiting our discovery, inspired me from the beginning. Episodes like The Devil In The Dark taught me not to judge persons or situations by their initial outward appearances.

Thanks to Star Trek, from my youngest days I grew up dreaming of a world where humanity would learn to live together in peace and venture out to seek knowledge amid distant stars.

PS: When writing Star Trek characters, are there specific dos and don’ts from the Star Trek folks?

DM: The first thing to keep in mind when writing licensed fiction is that the licensor (aka, the owner of the copyright) expects officially licensed derivative narrative works, which the industry often calls “media tie-ins,” to be consistent with the continuity, tone, and characterizations as shown in the canon, which for Star Trek comprises all the officially produced episodes, short films, and feature films.

We need to capture the characters’ “voices” — Spock has a particular style of dialogue, as does McCoy, etc. Some of the typical restrictions one encounters on any media tie-in project include not establishing any new family members (either living or dead) for the canon characters; not permanently altering the principal characters’ marital status or physical condition; and not establishing details that contradict anything already established in canon as it exists at the time the tie-in work is created.

With regard to characterization, it’s important to remember that most of the main characters in Star Trek are intended to be “good guys,” so the licensor is unlikely to approve story proposals that involve our heroes resorting to extreme violence, war crimes, etc., to resolve a story issue.

For instance, if one were writing a tie-in story featuring Captain Benjamin Sisko from Star Trek: Deep Space Nine taking on an entrenched foe, one might recall that Sisko resorted to borderline amoral tactics against the Maquis in DS9 canon. But that wouldn’t necessarily be a license for him to do it again. For instance, if the tie-in were set before that canon incident, one would have to assume he had not yet been pushed to that extreme; if the story were set after that canon event, then one might be encouraged to emphasize Sisko’s internalized regrets about what he did, and then have him find another way to resolve this story’s narrative conflict.

As a general rule, while characters can experience small personal epiphanies and insights at the end of tie-in stories, writers are encouraged, metaphorically speaking, to return the Star Trek toys to the box in pretty much the same condition as which we found them.

PS: Talk me through your process for a Star Trek novel. What are the “beats” they MUST have?

DM: There is no such formula or mandate. Each original Star Trek novel is crafted by its author(s) and editor(s) from scratch. The story arcs, character arcs, and individual “beats” that constitute those tales were devised as needed or desired to tell the stories their creators wanted to tell.

There is no edict that “every TNG novel must have a briefing room conference scene,” or that “every Discovery story must end with someone crying,” or that “every Star Trek novel must include a space battle.”

For instance, my most recently published Star Trek book was the Picard novel Firewall. The genesis of that novel was a simple invitation from one of the editors: Would I like to write the story of how, when, and why Seven of Nine joined the Fenris Rangers? I said “yes” and then I went to work thinking about the story I wanted to tell.

The few requests I was asked to accommodate were to make sure that some elements of the book grounded it as part of the Star Trek: Picard continuity; ensure it respected any relevant canon details established in Star Trek: Prodigy, and that Seven of Nine must not kill anyone.

With those limitations and requests in mind, I researched all the canon information I could find about Seven’s backstory, and about the Fenris Rangers. I pulled lines of dialogue from scripts and analyzed them, word by word, looking for clues to Seven’s motivations and to the timing and sequence of events. I cross-checked those details against Star Trek chronologies. I consulted the Star Trek: Star Charts maps, as well as real star charts from the European Space Agency, to confirm information about where certain fictional worlds would be located.

Then I wrote a massive outline, more than 40 pages long, detailing the story, along with Seven’s motivations, for review by my editor and the licensor. I chose to structure my story as a classic Bildungsroman, or coming-of-age tale, and to emphasize Seven’s journey of self-discovery as a queer adult woman only belatedly finding her independence and forging her own path in life. None of that was dictated to me by the editor or the licensor. I decided what to emphasize, and how to present it. I created the supporting cast. I crafted the plot. That’s what they paid me for.

After some back-and-forth with my dear friend Kirsten Beyer, who oversees tie-ins based on the new Star Trek series created by Secret Hideout, I revised some of the dramatic scenes involving Seven and Janeway to make them less melodramatic and more grounded in an honest difference of vision between two characters of good intentions. Thanks to Kirsten’s astute feedback, the story of Firewall was greatly improved.

Once the outline was approved by Kirsten, the editors, and the licensor (CBS Studios), I wrote the novel manuscript, which then went through the same kind of vetting process (which was quick and mostly involved minor tweaking of elements here and there), and then it was delivered for the usual production process of copy editing, layout, proofing, and printing/binding.

PS: Which Star Trek race intrigues you the most?

DM: My answer to that question is always changing. It used to be the Klingons. Then, for a time, I obsessed over the Trill. Around 2010–2014, I had a lot of fun establishing a bizarre secret culture for the Breen that reconciled all of the on-screen contradictions about their physiology and appearance. I also made a few forays into the exploration of synthetic sentience, with my Cold Equations trilogy and my Section 31 novel Control, and into hyper-evolved post-biological species in my Destiny trilogy, as well as in the Vanguard saga.

These days? No idea. I’ll have to see what strikes my fancy next week.

PS: In all of the Star Trek timelines, who is the most difficult character to write to your own satisfaction?

DM: I never got the hang of writing anything involving Chakotay. I simply could never get a “feel” for the character. I’m not really sure why that is. I can picture Robert Beltran as the character; I can hear his voice and the cadence of his dialogue. Where it falls apart for me is when I try to imagine what’s happening inside his head.

PS: Of the canon Star Trek alien races, who have you enjoyed writing most?

DM: I can’t really say I have a favorite among them, but I have to confess I had a lot of fun making the Borg as terrifying as I could in my Star Trek: Destiny trilogy. I imparted powers to the interiors of Borg cubes that hadn’t been seen yet in canon at that time, such as the Borg’s ability to reshape the interior configurations of the cubes almost at will, and the ability of the cubes themselves to attack and repel intruders. Between that and being allowed to speculate on one possible origin and final fate for the Borg Collective, writing about the Borg was a total blast.

PS: Let me ask you for your thoughts on four specific characters in terms of what makes them tick. Let’s start with Seven of Nine.

DM: Good choice, as I’ve recently spent a lot of time inside her head while I wrote Firewall.

Seven is a mass of contradictions. Beautiful but terrifying. Aloof but lonely. Powerful yet vulnerable. Arrogant but self-conscious. Her assimilation at the age of 6, followed by her forced severance from the collective at the age of 24, left her with serious psychological trauma.

During her first few years after emancipation, she was socially awkward, neurodivergent, and had serious difficulty reading others’ social and emotional cues. She was adept at analyzing others’ physical cues and extrapolating conclusions from them about those persons’ reactions and intentions, but it took her a long time to develop a true “theory of mind,” an ability to project herself into the point of view of another being with whom she is not united via a hive mind.

Even by the end of the Voyager television series, Seven had not yet developed a genuine sense of human empathy. This, coupled with the fact that her childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood — in essence, the most important formative years for the personality — had been stolen from her by the Borg, caused me to find her depicted romantic relationship with Chakotay (an authority figure on the ship, and almost her surrogate father figure) awkward and ill-advised.

Despite all this, something deep inside Seven wants to connect with other people. She wants to be a protector. She wants to defend the weak, perhaps to make up for the fact that no one protected her. This can be seen in her devotion to the XBs, particularly Icheb, who came to live aboard Voyager during the series’ final season.

But her desire to help, to take meaningful action, leads her to frequently clash with authority figures. Despite her time in the Borg, she is not a team player by nature. She wants to be a lone wolf. To exercise her own judgment without being second-guessed. To mete out justice as she sees fit. The only mitigating aspect to this part of her persona is her need not to lose the trust of, and bond with, Kathryn Janeway, her surrogate mother figure.

In other words, Seven was born to be a Fenris Ranger.

PS: Dr. Bashir.

DM: Another character about whom I’ve spent a lot of time writing. In his youth, his defining trait seems to be his naivete. He acts like a wide-eyed boy playing hero on the frontier. In his heart, Julian Subatoi Bashir has always been a romantic and a dreamer. If his parents hadn’t broken the law to have him genetically enhanced as a child, he might have grown up to write holonovels. Instead, he longed to be a hero, a savior, a martyr. He knew he had been granted an amazing gift of intellect and abilities, and his risk-taking seems grounded in his need to “earn” those gifts.

Because he grew up harboring a dangerous, potentially career-ending secret, one that eventually got exposed and landed his father in jail, he seemed to have trouble forging bonds of love or affection with the non-enhanced. Maybe this is what drew him to become friends with Garak, another person who concealed the majority of his abilities.

But then came Section 31. They misjudged him. They assumed his enhancement would make him an easy mark for recruitment. Instead, he sees them as traitors, criminals running an extralegal, unsanctioned, interstellar dirty-tricks conspiracy. They became the villain he had longed to fight all his life. Something vast, mysterious, and powerful — a foe equal to his gifts.

He’s insane, obviously. Section 31 will eat him alive. But Bashir, the consummate Quixotic hero, will tilt at that windmill until either it or he is gone.

PS: Sulu.

DM: His defining characteristic is devotion, of the sort that drives a person to excel, to do a perfect job even when no one is looking, when no one will know. Because Sulu himself will know.

He prides himself on excellence in the performance of his duties — as a physicist, as a pilot, as a swordsman, as a ship’s helm officer, as the commanding officer of the Excelsior. He also found time to balance his work with having a family and raising a daughter, Demora Sulu.

But his strongest devotion is to his comrades-in-arms from the Starship Enterprise. For them he was willing to risk everything — his career, his reputation, his life — when Kirk asked for his help to save McCoy’s mind and Spock’s soul. Sulu is a faithful friend to the very end of the road.

PS: Deanna Troi.

DM: I know this seems too obvious, but she runs on empathy. Not just her ability to experience the emotional reality of others, but her ability to persuade others to open themselves to the idea of caring about the feelings of beings other than themselves.

To Troi, empathy isn’t just some psychic talent she inherited as an accident of birth. It’s a way of life. It’s a worldview that is predicated on building bridges between even the most disparate points of view and fostering mutual understanding as a path to ending violent conflict once and for all.

PS: What is the psychological difference between writing stories based on Star Trek: The Next Generation and Star Trek: Picard?

DM: Hope versus cynicism. Optimism and hopefulness are embroidered into the very fabric of Star Trek: The Next Generation. The bulk of the series is committed to the proposition that we can and will choose to follow the best angels of our nature, given the right circumstances. People forgive old slights in TNG stories. Conflicts are brought to an end. Mysteries are unraveled to reveal wonders, and even the most dangerous of foes are kept at bay by clever tricks or by appeals to compassion or self-interest. The message of TNG is, “It will get better.”

The message of Star Trek: Picard is, “No, it got worse.” People went back to being dumb, panicky animals. Prejudice made a comeback in the Federation. Defeatism took hold in Starfleet. Heroes lost their faith. Institutions lost their senses of purpose. Alliances crumbled. Networks collapsed. The weak and vulnerable have been forgotten, abandoned, or given short shrift. No one learns from their mistakes.

If the point of TNG was to say, “Have courage—we’re all in this together,” the overwhelming message of Picard seems to be, “Tough break, kids—you’re on your own.”

PS: What characters have surprised you most in terms of what you are able to discover within them?

DM: Oddly enough, all the Mirror Universe versions of our regular characters. Unlike DS9 and Discovery, which took a high-camp approach to the Mirror Universe, I approached it as just one more expression of the multiverse and tackled its narrative head-on, as a serious tale of the downtrodden throwing off their chains and rising up against their oppressors.

Characters I thought I knew took on all kinds of new dimensions and shadings in this darker setting. Some who were heroes became villains, and vice-versa. But by treating their desires and pains with sincerity, they became complex, multifaceted persons, and the tale of their fight for freedom became something truly epic.

PS: What challenges are unique to writing Star Trek: Discovery stories?

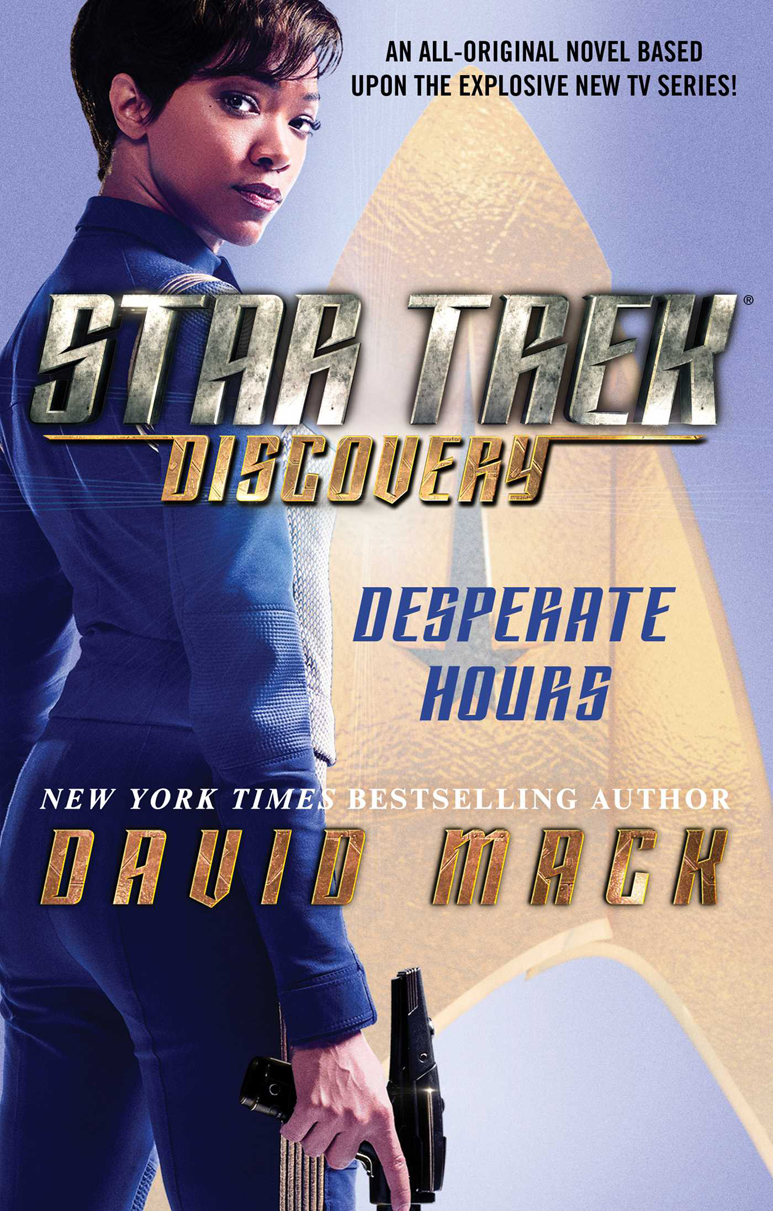

DM: I’ve written only one Discovery novel, but from my perspective, writing Discovery stories set early in the series’ continuity bring the risk of setting any Star Trek tale in a prequel period of the franchise’s history: the danger of having one’s story overwritten by later-established canon.

To a degree, this happened to me with my Discovery novel Desperate Hours. I wrote it based on the production drafts of the season-one teleplays. Because of the longer time it takes to push a book through production, its contents had to be locked down fairly early in the process. By contrast, the producers sometimes fiddle with overdubs and re-edits of episodes until hours before they transmit the final version to the network for distribution. This is why Burnham’s memory of her parents’ death in Desperate Hours doesn’t quite match the flashback seen in the pilot episode; the televised version was written, shot, and inserted after my book was printed.

By the same token, when Desperate Hours was commissioned, Discovery series creator Bryan Fuller assured me and my editor that the show had no plans to ever include the Enterprise, Captain Pike, or Spock, and that was why he wanted the first tie-in book to be a story about Michael Burnham and Spock and the Enterprise under Pike.

So imagine my surprise when season one of Discovery ended with the ship meeting the Enterprise, and season two involving Pike and Spock interacting with Michael. That happened because Bryan Fuller left the show before shooting started, and the new showrunners, Gretchen Berg and Aaron Harberts, decided they wanted to include Pike, Spock, and the Enterprise.

As for writing Discovery stories set after their jump to the 32nd century, I have no idea what challenges that might present, as I have not been involved in writing any of those books.

PS: I loved your Discovery novel Desperate Hours! It felt like I was reading a movie. Was that intentional?

DM: Absolutely. Before I wrote novels, my formal training and college degree were in screenwriting and film/television production. I’ve always loved movies, and I like to think I bring a cinematic style to my stories, at least in terms of the kind of scope I prefer for my action sequences. All of my novels’ big set pieces look amazing in my imagination, but they each probably would cost around $200 million to capture on-screen.

PS: What do you feel are the biggest flaws (if any) in Starfleet?

DM: As depicted on-screen, it is top-heavy with officers. No navy, aquatic or space, can function with that kind of inverted-pyramid command structure. Realistically, there should be 10–12 enlisted personnel and or non-commissioned officers for every commissioned officer aboard a starship or starbase. Junior officers above ensign should be in charge of specific departments or units. And ensigns should rightly fear Master Chief Petty Officers, even though they technically outrank them. Also, for several specialist roles there should be Warrant Officers.

In terms of how Starfleet operates, its tactics, shipboard security, and general protocols are a mess. None of these folks would last a week with the cadets at Annapolis.

PS: There seemed to be a point in the Star Trek: Voyager & TNG series where we met a lot of planets that involved meeting the elders during harvest time. How do you avoid such cliches?

DM: Honestly, I don’t recall noticing that particular trope in either TNG or Voyager, but for the sake of discussion I’ll take your word for it.

As for how I avoid those particular tropes (or others that might be regarded as cliche), all I can say is that when I concoct stories, I’m always trying to craft the most dramatic entry points, the most exciting set pieces, and the most awe-inspiring locations. I want every element of my stories to evoke a particular emotion, both in the characters and in the reader.

To that end, if I start upon something that feels cliche or overdone (“the crew discovers a derelict starship in orbit”) I try adding a bizarre twist (“the twisted, wrecked hull of the derelict ship is entwined with the mostly dead body of a massive cosmozoan, as if they rammed into each other, or got fused by the biggest transporter beam in history”). The idea is always to push a first-level idea to become a next-level idea.

PS: What lessons have you learned from your Trek work that you’ve applied to your non-Trek novels?

DM: My work on Trek novels taught me a lot about capturing the nuances of a character’s “voice.” The kinds of words they use. The lengths of their sentences. Catch-phrases. Verbal tics and physical habits. All the details that one can use to bring the character to life on the pages of a tie-in novel. That skill is transferrable to any media tie-in project (such as my novels for 24, The 4400, or Wolverine) as well as to original novels. Once I learned how characters’ “voices” are created, I was able to apply that knowledge to style the voices for my own original characters, and to make each one feel distinct from the others.

PS: Which of your Trek novels is the easiest to grasp for a more casual reader not well-versed in Trek canon?

DM: It depends. If the prospective reader is passingly familiar with Star Trek: The Original Series, but not with any of its spin-offs or the movies, I might recommend the nine-book Star Trek: Vanguard saga, starting with its first volume, my novel Harbinger.

If your imaginary reader has encountered the Rick Berman-era Star Trek series (TNG, DS9, Voyager, Enterprise), but not TOS or the more recent series, I might suggest they take a chance and grab the omnibus edition of my Star Trek: Destiny trilogy. It’s an epic crossover of TNG/DS9/VOY/ENT in which all necessary backstory is explained. Some of my fans have referred to it as “the Lord Of The Rings of Star Trek.”

If your casual reader has some knowledge that the Voyager series existed and that Seven of Nine is in Star Trek: Picard, then a great jumping-on book that requires no warm-up reading is my latest novel, Star Trek: Picard – Firewall.

PS: Can we look forward to more Discovery novels from you?

DM: Not at the moment. I’m not presently under contract to write any more Star Trek novels, and, regrettably, I have no idea if or when that might change.

PS: What are six Star Trek novels you think we all should read?

DM: I’ll try to restrict this list to Star Trek books that I did not write. In no particular order:

1. Star Trek: The Next Generation – Imzadi, by Peter David

2. Star Trek – The Final Reflection, by John M. Ford

3. Star Trek: Deep Space Nine – The Never-Ending Sacrifice by Una McCormack

4. Star Trek: Deep Space Nine – A Stitch In Time, by Andrew J. Robinson

5. Star Trek: The Lost Era – The Art Of The Impossible, by Keith R.A. DeCandido

6. Star Trek: The Next Generation – Immortal Coil, by Jeffrey Lang

PS: What is next on your horizon as we write this?

DM: Not much, to be perfectly honest. I have a scriptwriting job for an audio drama project, but it hasn’t been announced yet, so I can’t say what it is or who it’s for. Other than that, I’m trying to get some sample chapters together for a new original contemporary fantasy novel that I’d like my agent to shop around for me, but I’ve got a long way to go before that’s ready.

###

All photos are copyright their respective owners.

Table Of Contents

Contact