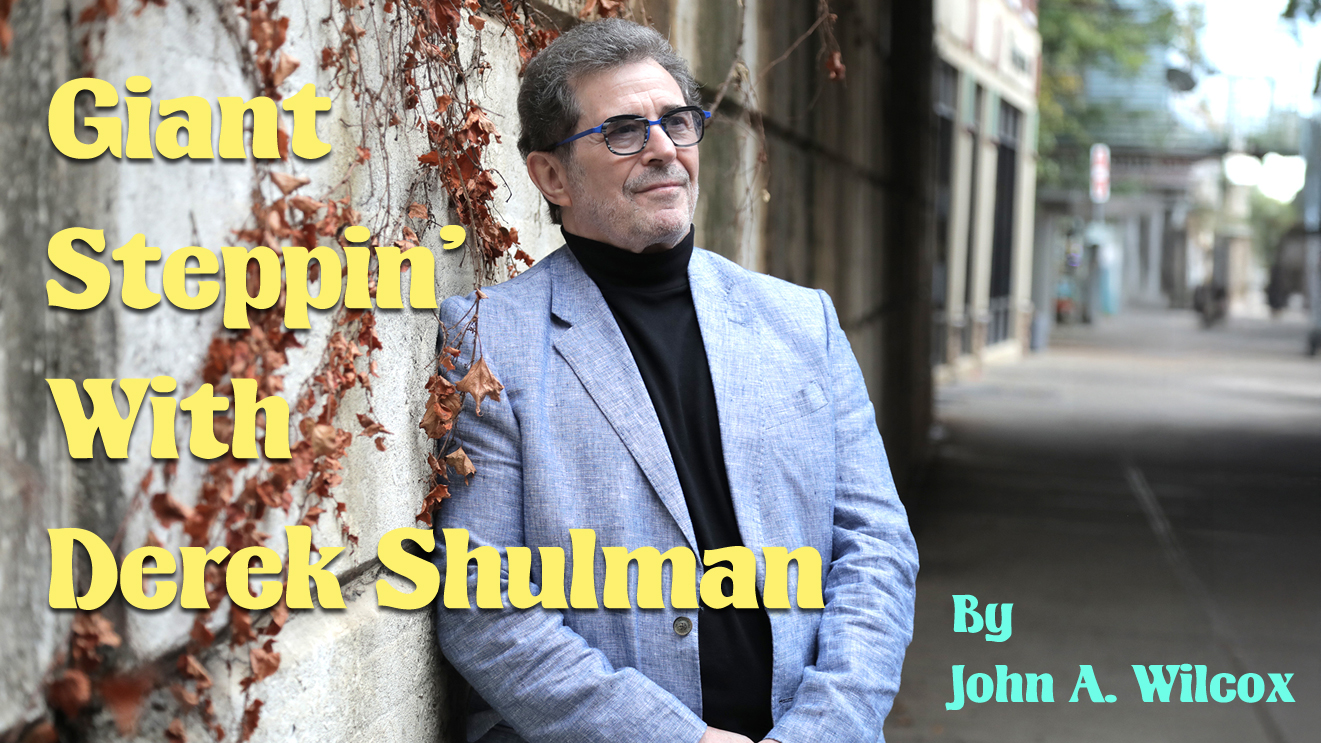

Giant Steppin' With Derek Shulman

By John A. Wilcox

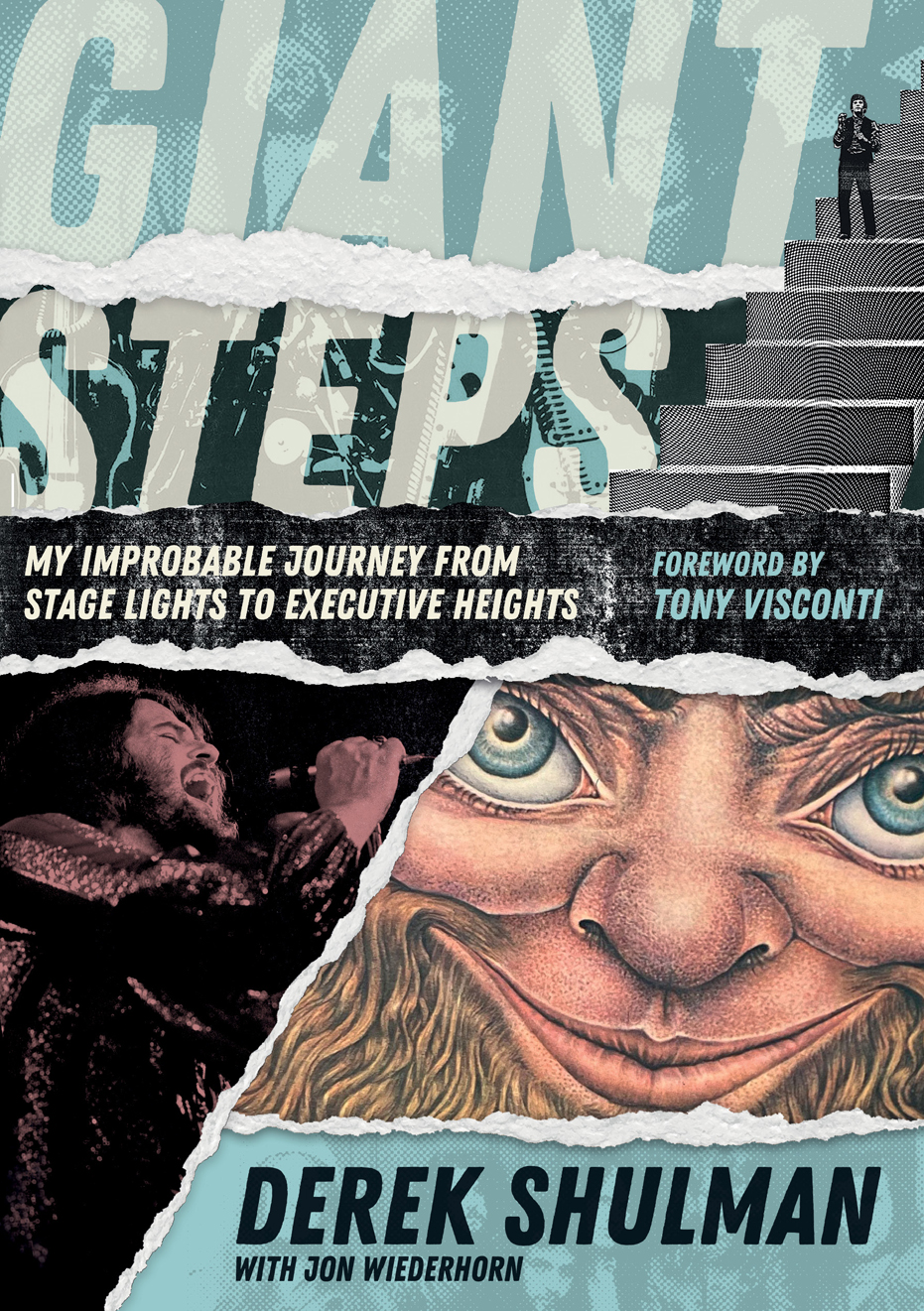

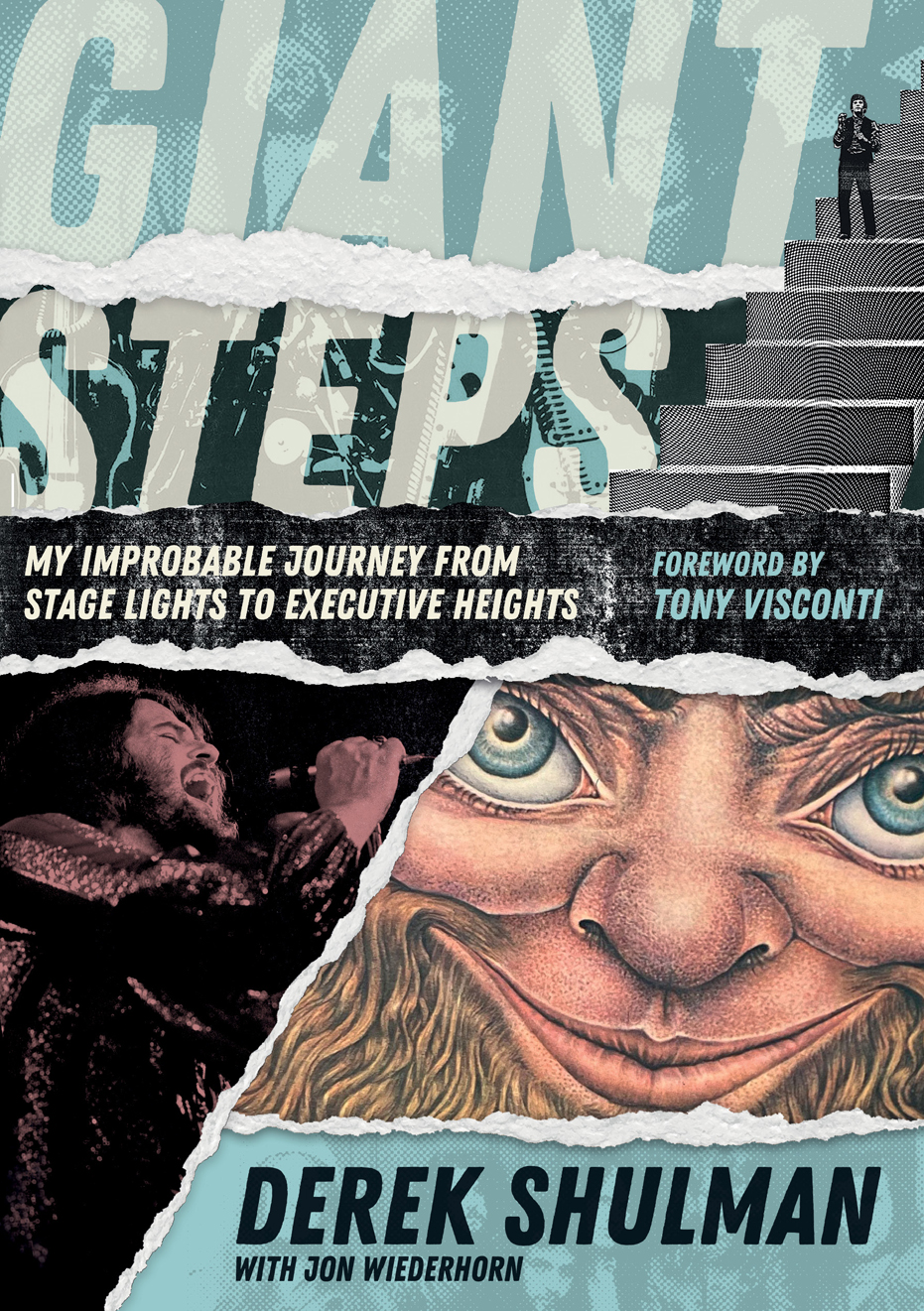

Since 1976, Gentle Giant and Derek Shulman have been a part of my life. When I heard that Derek Shulman had written a book and would I like to interview him about it, I pounced on the opportunity! The book is Giant Steps and it is a fascinating look at his storied life. We sat down recently for a chat, and here are the results...

PS: I found the book to be very emotional.

DS: Well, that was my intention. Not just to be behind the music, if you like. It was my intention to show something which we all go through in various forms. I mean, I'm not a machine. It's not just about the rock and roll lifestyle of rehab and drugs and party on dude. It's about the real world in music.

PS: It also struck me as being a lot about

family.

DS: That too. I mean, as you said, emotional.

There are reasons why you are who you are and you have to dig in through therapy,

in my case, and everything else. As well as what's important to you.

As well as music, which is the most important thing in my life. But more important than that is my family and siblings and everything else.

So I wanted that to come across as it did with you, and I'm happy about it.

PS: What inspired you to write the book?

DS: Well, actually, I had no intention of writing a book way back when. But a friend of mine,

of ours, my wife and myself, who was the book editor of the New

York Times book list - this is before COVID.

We'd have dinner, and I'd tell him stories about the various artists I was

dealing with and the various adventures. And he would say, you know what? They're really

interesting stories. You should write a book and I said, yeah, I'm like, okay. I write lyrics, but I'm not a writer. And he persisted.

I started writing before COVID, but you have to dedicate yourself two or three hours a

day, shut everything else. I wasn't able to, to be honest with you. And then COVID

did it. And everything shut down.

I got COVID,

actually. I was one of the first, which is not good news. But the good

news is that it didn't travel very far. Basically I was isolation for 6

weeks with a TV and a laptop. I started

in on where I'd left off a couple of years before. I think perhaps that

was the reason why the emotional part came out because I figured "Okay,

what am I going to write about?" And to be honest with you, my daughter-in-law's father, had COVID at the same time as I did,

and died from it. So that was a real wake up call to kind of

expose myself. About why I am who I am, because I led off with my father's death and me being

there. And that was a trauma which you never

get over, even after 70 -plus years. I mean, I did get over it,

but it affected me. So what I wanted it to convey was we all have these reasons

why we are who we are. I don't want to say it's okay to be like that. So it's

just to feel the way it is you do. And it's okay to be family oriented.

But what I also had from, again, my father was, actually, his DNA.

As did my siblings. Music was everything for him and it was and is for us.

PS: If music is everything to you, why did you stop doing it?

DS: No, I didn't stop.

PS: Well, I guess I should say - publicly.

DS: Okay.

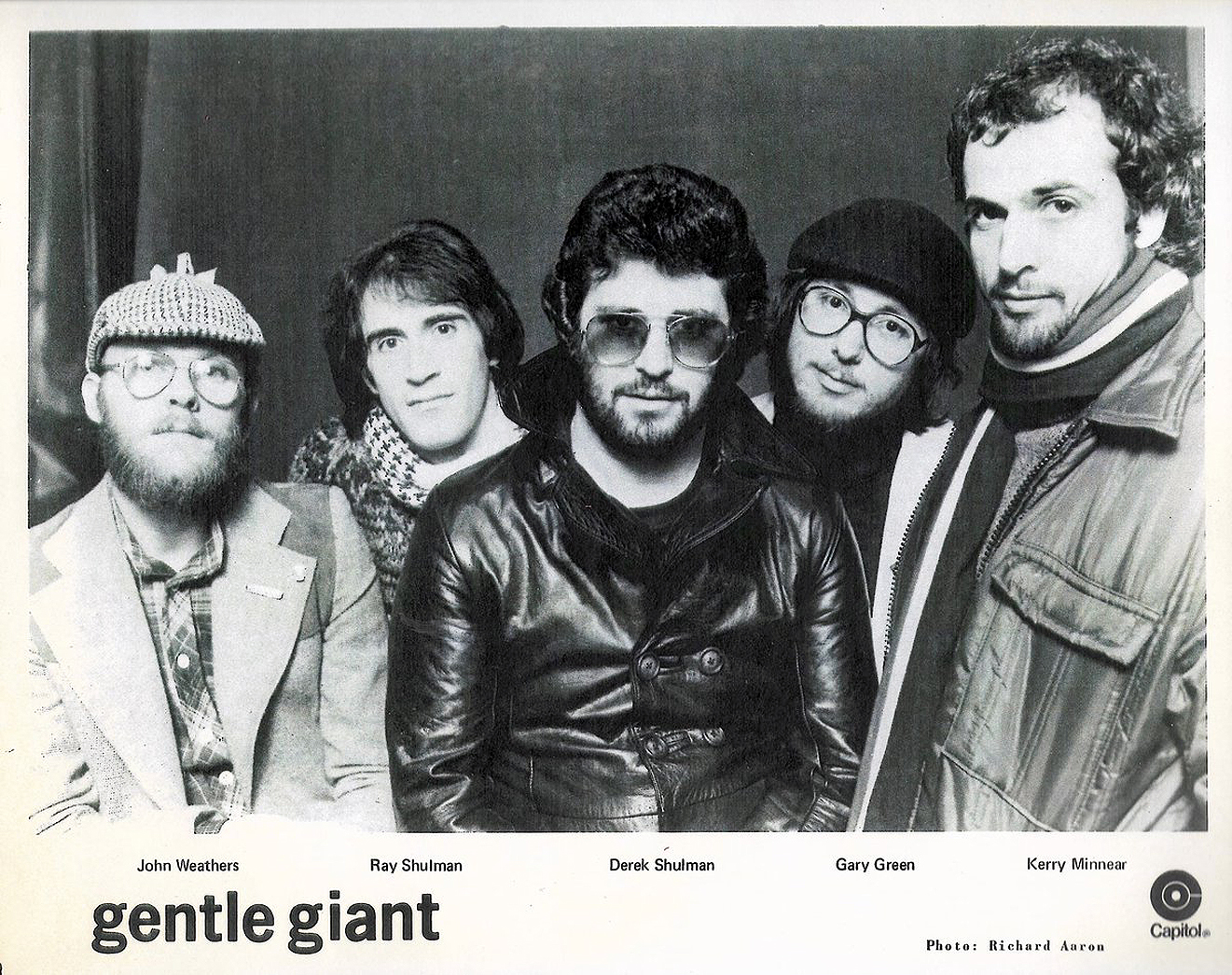

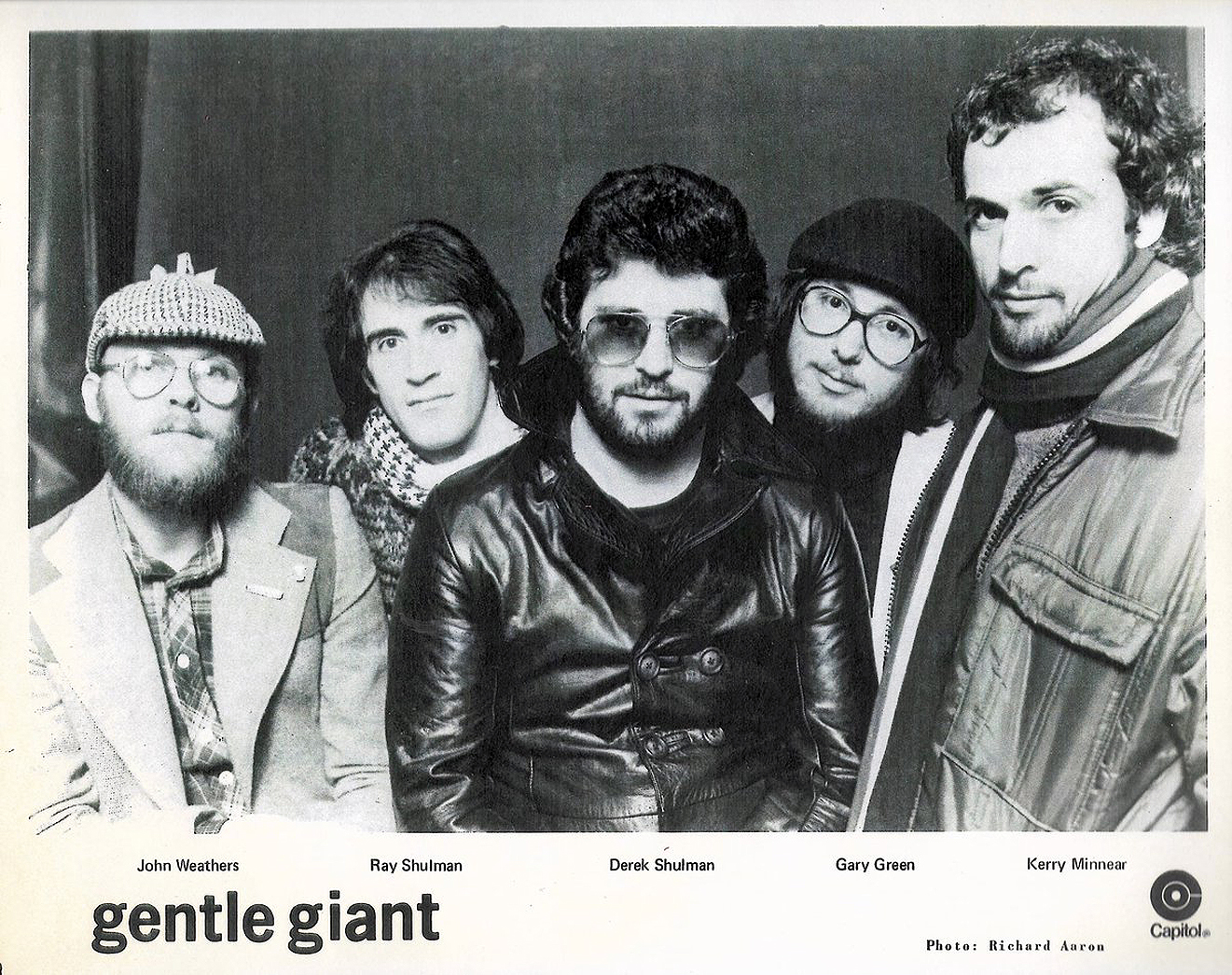

Well, okay, publicly, because Gentle Giant, as an entity,

and create a creative force, had run this course, honestly.

And as we've discussed about family. I and Kerry,

our keyboard player, we had our first kids.

And knowing that, having been in a house where my father was a

musician. And seeing how it can affect you. Also my brother

Phil who left in 1972, the reason why he left the band was because he had a

family. That's the reason, one of the reasons,

should I say, that we said, okay, look,

we should stop now why we're still kind of on top or why we're still an entity.

And also at the same time, to be honest with you, the creative juices were dwindling as well as the marketing tools that you're able to utilize , and our audiences were dipping

slightly and what we didn't want to become our own tribute band. Or a band that were legging around, playing the old, the old music when we were not able to

get into our size 30 pants anymore. So it was a time to say stop.

And 20 years ago and before, had lots of offers from even Live

Nation to put the band together for tours. Honestly it was a

period of time where the chapter closed. It was an

incredible chapter to be in Gentle Giant but it was closed and i we didn't

want to open it because we can't really create something that is already part of

history. I don't know if I'm making sense.

PS: You're making perfect sense.

DS: As far as music is concerned, I re-invented myself to a certain degree on the other side of the fence, and I used my experience as a musician as well as someone who understood eventually

why bands broke and why they didn't. To help other bands who I had

signed. I made a

fairly good living on it, so music was always part of my

life. And it still is.

And I'm sitting in my study here, and I'm looking at a

song, and the bass, and on my computer.

I'm in the middle of remixing the one album that we weren't able to remix.

Well, Steven Wilson wasn't able to. Because we didn't have the multi-tracks, which was In A

Glass House. I'm in the middle of remixing that in Brooklyn,

in an incredible studio that has the highest end AI,

which was able to take out, not just with stems, but the actual tracks.

It's a new system, which is incredible.

PS: Is that similar to what I guess I call the "Peter Jackson" thing?

DS: It's actually way

beyond that. I'm in the middle of it, remixing that. It is like that,

but much more updated.

PS: Cool. I've always been dissatisfied with the CD versions of that. I imagine a lot of that was technology of different eras.

DS: Right, of course. You know, today the technology is fantastic in that you can actually do

the things we couldn't do. The things we had no time for nor the ability to do back in the

day. Steven Wilson, you know, has been a great friend and has basically remixed

most of the catalog. We just put out the one he didn't do - Playing The Fool, and that just came out a little while ago.

That's actually a really, really

good album. It's not just a good album, but it's a really good remix.It was a guy called Dan Bornemark,

who has been the band's archivist for many years. He's

also a brilliant musician, and he has a studio in Sweden. He was able to listen to the shows multitracks,

and really dig in and make sure that what you had was exactly

the show that was presented and not just some of the show, like the original album. So that's something we were ever happy about. But yeah,

the fact that I'm doing In A Glass House, I think that would be fun for people

to hear it the way that we would like to represent it.

PS: Once it's all mixed, are you just doing a CD? Are you also doing a more

immersive, like a surround version or things like that?

DS: Oh, that's 5 .1 Atmos,

the whole thing. Yeah, it sounds amazing with Atmos.

PS: I can't imagine I'm alone

in appreciating the effort that bands are doing for the listeners and

hopefully for themselves.I imagine as you're going through something like that

where you can really isolate everything it's got to be a treat to

hear it at that quality now.

DS: Yeah, it is.

I mean, let's get back to the live album - Playing The Fool. We wanted to present it the way we heard it on stage.

So you're right there. So you could hear the band's banter on stage. And if

you're in front, you know, you got to hear the banter. So here on In A Glass House, you're able to hear the transients and all

the other sounds of instruments that you couldn't hear..

PS: Where was the band's head at the

time of that album?

DS: Well, it was kind of somewhere else. It was the album after my brother Phil left. And having been in Gentle Giant, and previously, in Simon Dupree And The Big Sound and

being a sibling, there's

a lot of sibling rivalry in the

band. And that was the first album that he wasn't part of. It was a very strange emotional time.

And it was almost a jagged edge to who we are and what we are doing. It was a hard album for me because we

did it very quickly because we had to get an album out. It was a feeling of being a five-piece as opposed to a six-piece.

During that album, I always felt that hearing it was an emotional situation. And the emotional part of that

was a jagged sort of album. But now I'm listening to it again in the way

that we probably should have listened to it back then. And it's actually really a

great album.

PS: Oh, yeah.

DS: I'm listening to it for the first time. Now I'm remixing it, and it's really, really good. It's just

surprisingly good. It's just weird to me to say that out loud. But I'm now hearing it the way we should have listened to it and and I can reflect back and hear things that I'm just amazed that

we did to be honest with you.

PS: Over the years did you ever get did you

ever get feedback from Phil of what he thought of the album?

DS: Not really because it was a period of time about three or four years when he left, that we weren't in touch. Because we were very angry, you know,

myself and my brother Ray, who passed away a couple of years ago, unfortunately.

He was flip-flopping all the time and making it very

difficult for the band to make decisions.

But we're in touch every every week now. He's never commented on the

music we made afterwards honestly. It was a period

he went back and did other things with his family. And that's in fact what he

should have been doing. We were angry. He was angry. But he made the right decision, ultimately. So he hasn't commented

on any of the music that he wasn't on since then.

PS: It makes a sense to me because none of my siblings ever asked me even one question about anything I did nor

asked to see any of it because it wasn't the space I occupied in their lives.

DS: That's very interesting actually. I had advanced copies of

the book. And the very first one I had, I sent to my brother Phil.

And we got on the phone. He lives in England. And he said, I didn't know you were involved in so many other things. But, you know, I guess he'd gone on being a family man, and he became a teacher again, and then ran a

gift shop. And even though we saw each other and we talked when

I went to England, his interest was the same as your siblings. We didn't talk about what I was doing or who I was with. But having read the

book, he was just amazed that he said "I'm amazed at what you did."

It just surprised him, which is pretty bizarre, you know.

But such is life and such is rival siblings, and you really realize

later in life, what these things mean.

PS: When you transitioned to working in A and R,

what satisfaction did that bring you musically that you did not have as a musician

yourself?

DS: Well, there's several things with that I could bring up. Obviously,

I made a very good living. I mean, I'm being honest. Of course. Toward the end of the group, I started looking after the business part

of the group and making sure that we had the contract, and everyone got paid, et cetera, et cetera. So I utilized that, and I was

able to work with musicians to make sure they got a fair deal as opposed to record companies ripping them off. And at the same time,

being with an artist and understanding what it was that they needed to have.

There was not one musician that could say to me "You don't know what it's

like." Because I certainly did everything. Yes I've slept on a bus.

Yes, I've been in places where you couldn't afford a hotel. So there's nothing that any musician could say that I

didn't do. And the fact that, you know, I played big places and tiny clubs and

etc. So I had that in my, if you like, repertoire as a record man.

And you're talking about satisfaction. To see the band,

the aspirations of musicians that I'm involved in come to fruition,

basically. And as long as the artist keeps their authenticity.

And that was key to me. You know, for most of the time, the artists I was very

involved with were authentic. They didn't try to be like anyone else.

All those bands that had authenticity and had something which was their

own and not following the leader.

But in retrospect, to be perfectly honest, it was fantastic when Bon Jovi's Slippery When Wet was number one. It was great when Pantera became

one of the biggest metal bands. I worked with AC/DC when they were being

dropped. I worked with them and they allowed me to work them because

they knew I was a musician. And brought them back from being dropped, to becoming AC/DC's back again with the Razors' Edge and Thunderstruck. Those feelings

are fantastic.

But there's nothing like, you know, in my old age here sitting down with a guitar here, sitting down with an open page, and thinking,

"What chord would work here?" And starting to put it down from your

own heart, your gut, and your head,

and creating yourself. So it was a fantastic period,

and I'm still involved. I'm friends with all the bands that I was involved with. But, now I'm really mixing, you know, one of the Gentle Giant albums.

And just hearing that, the feeling I get from that is a little bit

different. It's me. It's not someone else.

So it's me and the

band's creation, if you will.

PS: What advice would contemporary

Derek give to mid-70s

Derek?

DS: Oh boy, that's a good question!

Honestly, Derek wouldn't take it. You

know, we were very high-handed and knuckle-headed and he did what we did for what

we wanted to do. You know, that's something that the band, in whatever

fashion,

were about. And probably why the music is still relevant,

I'm gonna say that, because we were who we were, you

know, there was never any A &R guy involved and saying, you should do this and

you should ask. Whatever we did, it was our idea, whether good, bad, or indifferent.

But if you're saying what advice would I give myself back in the day,

I'd just say to not listen to anyone. To be yourself, to be authentic,

and be real. And if you are, and be really good and

not get involved in anything that will screw your head around. So, I'd give myself the advice that I gave myself back in the day!

PS: Back in the day, there were much fewer avenues to release music. Now you are like a BB in an aircraft hangar.

DS: Well, that's probably true. I mean, the jigsaw puzzle back in the day was maybe

100 pieces. Now it's a million.

If you're a musician, and you really are a musician, and you're creative and

you want to do something that is yours - which is what we did. I mean, right

back, when we first started, and you want to be heard, and that's,

that's really, someone who you are, nothing should get in that way.

And you're not entitled to make a living. Let me just make that clear. No one's entitled to be, you know, "I'm

great, I'm great. I'm getting all these views and likes and everything. I'm entitled to make a living." No you're

not. You have to get up on stage and you have to be great, and

you have to get to get a fan to say "I want to see you again. I'm

going to pay this $10 or $20 Again." And if you go somewhere else, you'll do that.

That's the only way that being a musician today will help you. Having likes and looks and views and

getting AI to do your things or whatever does not entitle you to make a living

as musicians. Being really, really good and being creative and being authentic

really does. And then go out there and try and try your best. And if

you get fans that want to pay for you to see you on stage then then you can make

a living. You're not going to be rich or famous you know you can make a living. That's

what we did.

PS: The music of Gentle Giant seems to be reaching more folks than ever.

DS: Certainly reaching a lot of new audiences, which is great. Young audiences,

which, you know, there were plenty of young people when we were young. And they aged

and stuck with us. I wouldn't say more, I would say,

because in fact, even though Gentle Giant would seem to be a kind of cultish,

we played at very big venues in different parts of the world. I mean, we were

headliners in Italy, we played 20,000 seaters. We were in Germany,

in Quebec and in Canada, even in the US we played to 8-10 ,000 people. But again, we weren't as big as our

contemporaries in the prog world.

It's interesting that the Internet and the films that were taken, we have a lot of it, I guess. For whatever reason a

lot of people filmed us and the music that we played seems still relevant to a new generation of world musicians and that was what happened during COVID. I'll tell you a really fantastic one. My son Noah and Ray,

my brother, put together a fan video of the song Proclamation, and it became an event of the prog year. That was really heartening to see these young people playing different music, different pieces

of music with different instruments. And it was brilliant. I mean, I thought it was

superb. And it was, for the most part, a lot of young musicians who were learning

and would be as adept as we were.

PS: I always felt that the secret to the longevity of Monty Python was that their focus was timeless instead of trend-driven. The same holds true for Gentle Giant. There is no Gentle Giant Disco album.

DS: No, we came kind of close probably a couple of times, but that's a good analogy, actually, an excellent analogy about being the word authentic. I say authentic. I'm using it again and again, but

I think that's exactly what it is. As were the Beatles.

PS: I always kind of grimace

when people don't give love to Giant For A Day. In the end it's still good songs, very well played,

you know. I'm never going to say no to Friends or It's Only Goodbye. I love that stuff.

DS: I think we were bowing a little bit to what was happening with radio,

and what was happening with our peers, if you like, to a certain degree. We were aware of the way your music is heard,

certainly, we were still doing very well live. They were playing hit singles, and

I guess we tried our best in certain effects to do that.

But actually, it didn't happen because I think that had we carried on it

may have become a parody of ourselves, and that's something that would be a bit

awful for all of us.

PS: Another album I have great love for is

Civilian. That album is just a jackhammer of goodness.

DS: I agree with you. I

think it's one of our better albums. for a couple of guys in the band it wasn't.

Primarily because it was made in Los Angeles and not in England. And they felt like a fish out of water. And it was done knowing that we're in a new decade. And again, we were moving on,

but it was certainly a really, really good album. And it was

one way to hope to regenerate and refresh what and who we were and our

audience, but we didn't get the backing from the label and it didn't work. That

was the time we said okay we know we can see the writing on the wall.

PS: Tell me a great story about your brother Ray.

DS: Yeah, let me think. Well,

I don't think I mentioned that Ray, after the band broke up,

that he went on to become an A & R man himself, and signed and produced Bjork and the Sugarcubes. And the Sundays. And indie UK bands like Ian McCullough.

He co-produced Pump Up The Jam, if you'll remember that song. And then, after that, he became the go-to 5.1 remix guy with Steven Wilson. So he found his niche,

initially, as a producer himself. And Bjork, and the Sundays. Bjork especially with the Sugarcubes, a highly unusual band. But he saw

something in them like he saw in Gentle Giant, he saw someone that is different

and interesteing.

As far as other things with him, he was, as far as the band with

myself and my brother Phil and then Ray were three brothers. Me and Phil,

um,

were always going at it. He was the peacemaker of the brothers.

And then after the band was done, we became best friends. We were literally best friends as

well as brothers. And I'd see him, at least, when he stayed with me because I live in America. We'd see each other at least two or three times a year, and we'd talk all the time

about whatever we were doing. He had a place with his wife.

And I'd tell her about what we were doing there. So

It was a big, sad loss.

###

All images are copyright their respective owners.

Table Of Contents

Contact